Media: KTV

Story title: “Tatuazhi i trëndafilit” nëpër ngjyrat e jetës gjen dashurinë

Date: July 16, 2023

Linku: https://www.koha.net/shtojca-kulture/385374/tatuazhi-i-trendafilit-neper-ngjyrat-e-jetes-gjen-dashurine/?fbclid=IwAR1AE5vB0X1DvT8hI0eB13b05LUjdrYBXisc651t3oZRxdvmJ2HT0Cmkstc

By: Fisnik Minci

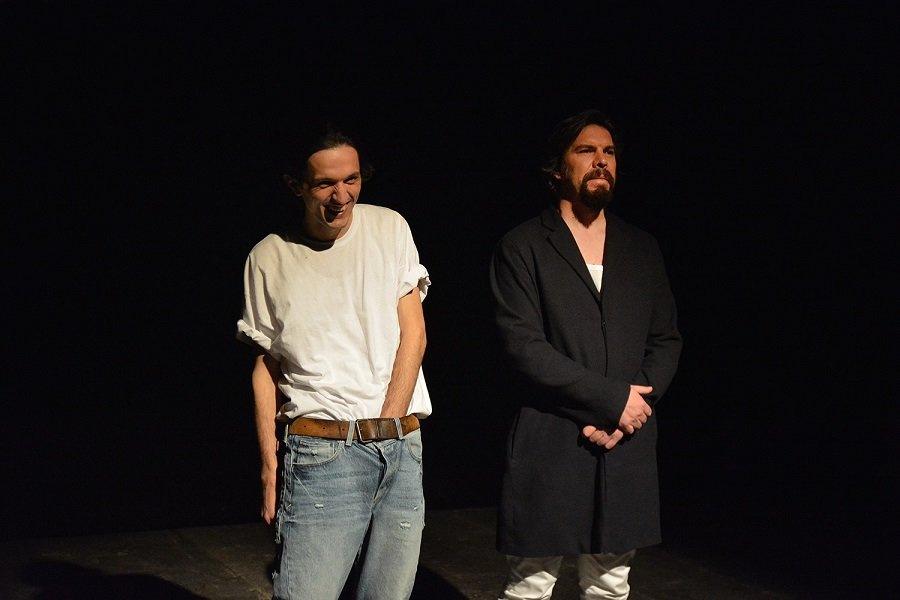

It has arrived as it was intended: a passionate tale of superstitions, promises and the possibility of love and passion after a broken heart. With an interactive approach with the public on the “black box” stage located in the Bosnian Cultural Center in Prizren, the well-known drama of Tennessee Williams, staged under the direction of Zana Hoxha, comes with the call to open the heart and find hope even where it is not expected.

The romantic comedy “Rose Tattoo” by the author Tennessee Williams, which remains a symbol of love, sex, emotional vulnerability and reproduction, was staged by the city theater “Bekim Fehmiu” thanks to the commitment of the director Zana Hoxha. The drama was performed on the ‘black box’ stage located in the Bosnian Cultural Center, integrating the audience into the game, who at the end of the show expressed their gratitude for the almost two-hour performance of the actors Aurita Agushi, Rifat Smani, Liridona Shehu, Alban Krasniqi, Xhevdet Doda, Beslidje Bytyqi, Valmira Hoti and Zana Duraku.

This drama is set in a small Sicilian-American community. There, Serafina delle Rose, played by the actress Aurita Agushi, is a fiery and passionate woman and mother, who, after the murder of the smuggler’s husband, shuts herself off from life and love. In the meantime, she often collides with her circle, while her daughter Rosa also faces the barrier set by her.

But the situation changes, when by chance a truck driver arrives at Serafina’s house.

The play, according to the description given by the city theater, is a passionate tale of superstitions, promises and the possibility of love and passion after a broken heart. In doing so, it offers a witty and interactive comedy with the audience, while reminding them to open their hearts and find hope where they least expect it. It also addresses the theme of sexual repression as a strong and ongoing theme, while turning her story into one of passion, romance and hope.

For the actress Aurita Agushi, this project marked the next collaboration with the theater “Bekim Fehmiu” in Prizren. She described the process of working with the resident actors as good, while also providing details about the challenges in interpreting her role.

“It was also very easy. I know the part very well, even Tennessee Williams is one of my favorite authors. This work on the Italian accent has been a bit challenging, I want to concentrate more on that. Even if I analyze the character of Serafina a little more closely, because she is a complex, multidimensional character, who varies throughout the performance, the tragedy that happened to her, then she recovers the love, prejudices and judgments that the circle makes of her, even here it is like I stopped and made a closer analysis and I believe that together with Zana, the director, with my colleagues, especially with Rifat (Smani), my partner on stage, we worked very closely and I believe that we did a very good job good”, said Agushi.

Xhevdet Doda, who played the role of Father De Leo, assessed that the environment created with the “black box” brought him closer to the public and at the same time expressed his satisfaction with the teamwork in this project.

“Satisfied with the performance of my role. It is a role that I have tried to give some artistic ‘sweetness’, of course with the suggestions of the director. I am very satisfied with the team, I am very happy for this premiere and I hope that this show will find its way to our audience”, said Doda.

The director Zana Hoxha has assessed that it is a project worked on with mutual love, where as a result the realization has progressed easily and with good energy.

“And almost like the show that gives a certain reality a little more rosy, a little different, more optimistic, and it was a kind of disappointment I would say, because we had to work in the original building of the Prizren theater and due to the renovation we decided here. But everything is good when it ends well, like tonight’s show that started with more dramatic moments then developed, the other colors of life came to the fore, because life has ups and downs, there are challenges but there is also a lot of love if we want to see “, said Hoxha.

University professor, director and playwright Fadil Hysaj was also present in the audience, who appreciated the acting of the actors, the work of the director and the reaction of the public.

“Let’s start with the actors, really an extremely beautiful play, a brilliant director, Zana Hoxha, a reading of a dramaturgical masterpiece by Tennesee Williams that in an almost authorial sense decomposed into one dimension, that a deep drama of a woman transforms, it gives life, it turns the comedy into a kind of liberation that conveys it, which we need. It is understood that the fight against evil, against suffering begins and is won within oneself, not outside oneself. It is also a very beautiful show, built with finesse, with a brilliant acting that I think is rare as such and I wish that it will have a long life on stage and that many, many people will see it”, said Hysaj.

This performance is the third premiere after the beginning of the renovation of the theater building. The first premiere was the show “Fausti”, a co-production between the “Bekim Fehmiu” Theater, the National Theater of Kosovo and the Gjilan Theater. While the second premiere was the play for children “Aphrodite again at school”. This year, the “Bekim Fehmiu” theater has performed the first cycle of staged readings of contemporary Kosovar drama.

Recent Comments