Skenë nga shfaqja “Kabare 1999” nën regji të Zana Hoxhës, e dhënë premierë në Teatrin e Qytetit të Gjilanit, më 5 shkurt 2026 (Foto: Rilind Beqa)

Nga: Berat Bajrami

Regjisorja Zana Hoxha, e bazuar në veprën “Cabaret” të Joe Masteroffit, e zhvendos ngjarjen nga Berlini i viteve 1930 në Prishtinën e vitit 1999 – një qytet i sapodalë nga lufta, plot me adrenalinën e lirisë së re, i përhumbur në erën e djegur të shtëpive, mungesën e njerëzve e lulëzimin e tregtisë së “më të fortit”. “Kabare 1999” është një realizëm i Kosovës së pasluftës që ende është në kërkim të të mësuarit për të jetuar

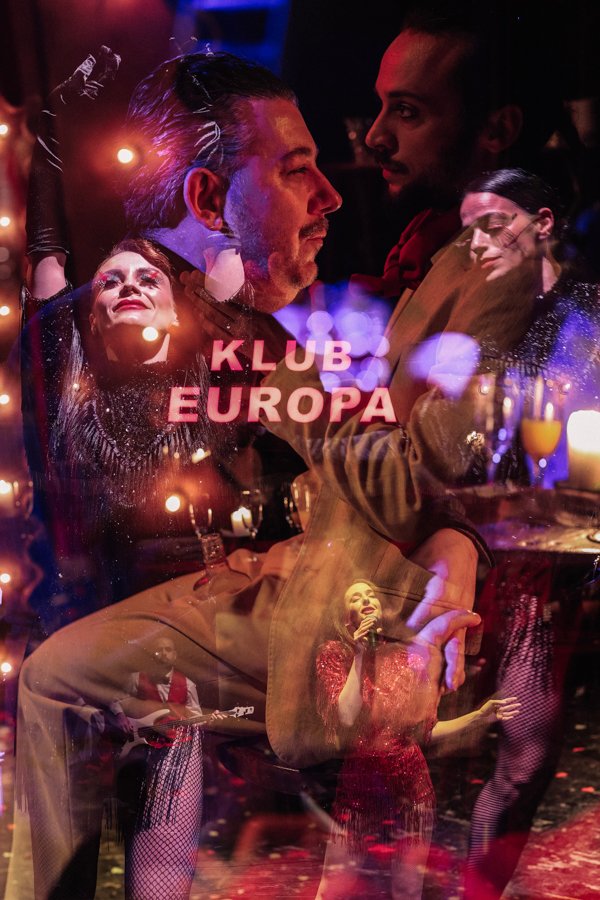

“Willkommen, bienvenue, mirë se vini…”, është thirrja që hap botën e “Kabare 1999”, një thirrje që tingëllon si premtim për festë, por që, sa më shumë zgjat shfaqja, aq më shumë kthehet në një ironi të hidhur. Mbrëmjen e më 5 shkurtit 2026, në Teatrin e Qytetit të Gjilanit, kjo kabare u shfaq si një hapësirë e ndarë mes dy botëve: mes dëshirës për të jetuar dhe tregtisë me plagët, mes lirisë së sapofituar dhe frikës së një sistemi që gllabëron secilin që guxon të jetojë i lirë.

Regjisorja Zana Hoxha, e bazuar në veprën “Cabaret” të Joe Masteroff, e zhvendos ngjarjen nga Berlini i viteve 1930 në Prishtinën e vitit 1999 – një qytet i sapodalë nga lufta, plot me adrenalinën e lirisë së re, i përhumbur në erën e djegur të shtëpive, mungesën e njerëzve e lulëzimin e tregtisë së “më të fortit”.

“Klub Europa” është flluska e “lumturisë”, e jetës pa probleme, e lirisë “së plotë” në shndritjen e dritave dhe magjinë e muzikës së pafundme. Aty ku jeta është qejf e plot ngjyra.

Paslufta në kërkim të të mësuarit për të jetuar

Zgjedhjet regjisoriale të Zana Hoxhës na sjellin në jetë personazhe të zakonshme në pamje të parë, porse gjithsecili e përplotëson njëri-tjetrin, secili ka peshën, ngjarjen, luftën dhe mënyrën e vet të konceptimit të jetës. Secili është kompleks, në të njëjtën kohë. Një realizëm i Kosovës së pasluftës që ende është në kërkim të të mësuarit për të jetuar.

Zymtësinë e përditshmërisë së pasluftës personazhet e ndrydhin dhe jetojnë mes dashnisë, seksit e qejfeve në Prishtinën që përqafon individualitetin e atyre që guxojnë, edhe pse të goditur ashpër nga lufta për mbijetesë.

“Kabare 1999” e shemb murin e katërt, publiku nuk është vetëm dëshmitar i ngjarjeve, ai është pjesë e saj me të qeshura e vallëzime. Personazhet janë të shkrira me publikun, të ulur edhe në mesin e tyre bashkëjetojnë momentet. Momente që rrjedhin natyrshëm dhe skena që të bëjnë ta humbësh ndjenjën e kohës. Rrjedhja e shfaqjes është organike, e pasforcuar – nga loja e aktorëve, balerinëve, muzikantëve, e deri te kostumet dhe skenografia.

“Kabare 1999” na sjell Kosovën e pasluftës jo si heroizëm të ngrirë, por si jetë e gjallë, e çrregullt, por ende e padorëzuar plotësisht (Foto: Rilind Beqa)

Një moment që e avancon teatrin vendor

Profesori universitar dhe regjisori, Fadil Hysaj, thotë se ky është teatri i vërtetë dhe “Kabare 1999” e avancon teatrin kosovar.

“Shfaqjet e mira nuk kanë moment, ato rrjedhin skenë pas skene. Ndihesh edhe komod në kuptimin e mirë, kulturalisht, por në të njëjtën kohë sheh se aktorët janë prej fillimit tërë kohën në një pjesë të një koncepti, në këtë rast që ka pasur Zana, edhe secili artist i pranishëm aty, prej balerinëve, kompozitorit, aktorëve, secili është i lirë. Ka një rrjedhë të magjishme dhe ka hapësirë me thënë atë që ndien dhe me thënë në mënyrën më të mirë të mundshme. Shfaqja ka frymëmarrje. Kurrkush, asnjëri prej aktorëve, s’do me tregu tash: ‘Unë kallëzoj çka di me bo’. Por ata luajnë me një koncept. Ky është një moment që e avancon teatrin tonë”, është shprehur Hysaj pas premierës së shfaqjes. “Ky është teatri i vërtetë kur kori vallëzon, kori këndon, krijon personazh, shpreh mendim, por në të njëjtën kohë të gjitha bashkërisht bëhen pjesë të një koncepti, edhe atë koncept e përpin publiku, e pranon emocionalisht në fund kur kryhet shfaqja, e kthen tek artistët me duartrokitje dhe i bën që mos me harru një ngjarje të tillë”.

“Harrojnë shtëpitë e djegura. Personat e zhdukur…”

Në qendër të shfaqjes është Aida, e cila e sheh qytetin me sytë e dikujt që dëshiron të besojë, të jetojë lirinë, e të ëndërrojë. Ajo përpiqet të mbajë distancën estetike, por distanca prishet nga varfëria, nga nevoja për punë, nga tërheqja ndaj Sonit, nga përballja me Claudion, nga kërcënimi i MC-së e bashkëpunimi me Ernestin. Ajo shprehet: “Më pëlqen ky qytet. Është vulgar. I rrëmujshëm. I zhurmshëm. Dhe të gjithë sillen sikur me ardhjen e lirisë të gjitha problemet janë zhdukur”.

Në këtë fjali ka një admirim dhe një ankth njëkohësisht. Sepse menjëherë pas saj vjen kujtesa: “Por harrojnë. Harrojnë shtëpitë e djegura. Personat e zhdukur. Familjet e shkatërruara.”

Kjo është drama e vërtetë e shfaqjes. Jo lufta – por ajo që ndodh pas saj. Momenti kur njerëzit duan të jetojnë, të këndojnë, të duan, të fitojnë para, të ndërtojnë një normalitet, ndërsa një pjesë e tyre ende kërkon të vdekurit.

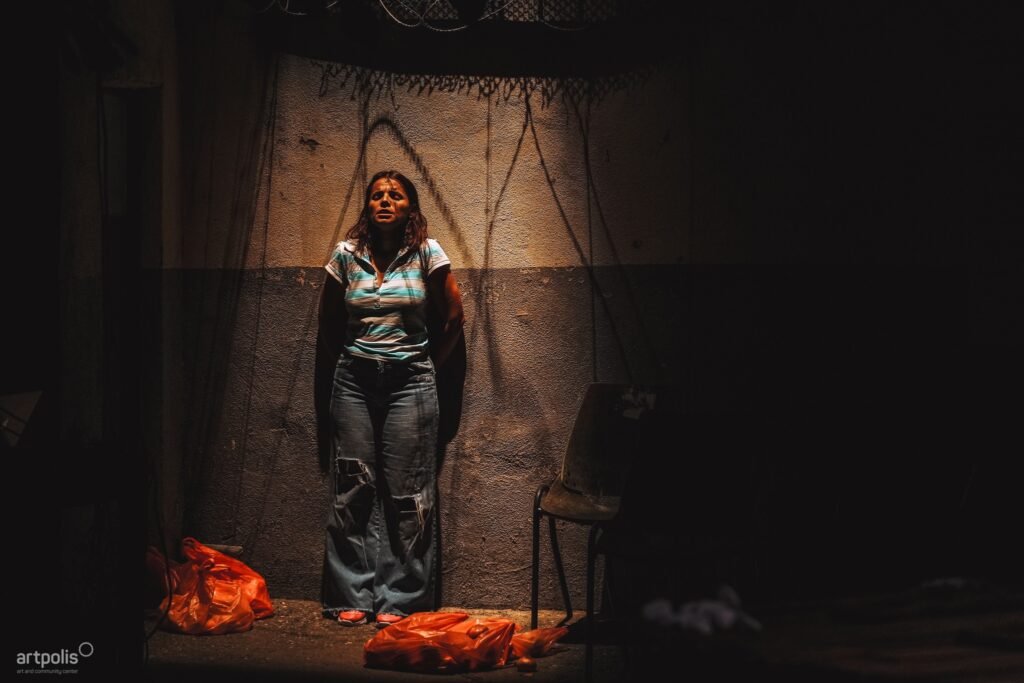

Në qendër të moralit të shfaqjes qëndron Shyretja, nëna që kërkon djalin e zhdukur, Fatbardhin. Ajo nuk është vetëm figurë tragjike; ajo është figurë ontologjike. “Kur ai u zhduk, emri i tij u bë ironi: fati nuk ishte më i bardhë, por i paqartë, i prerë në mes. I këputur nga lufta”.

Mirëpo Shyretja nuk e pranoi zhdukjen si fund, ajo vazhdonte të kërkonte informacione. Dhe kjo histori nis aty: te vendimi i saj për të mos e mbyllur kërkimin — “sepse disa histori ekzistojnë për të dëshmuar se fundi ende nuk është vendosur”.

Liria është të mos harrosh

Në këtë akt kërkimi që nuk përfundon, shfaqja e gjen një nga kuptimet më të thella të lirisë. Liria nuk është vetëm të jetosh. Liria është të mos harrosh. Është të mos pranosh mbyllje të rreme.

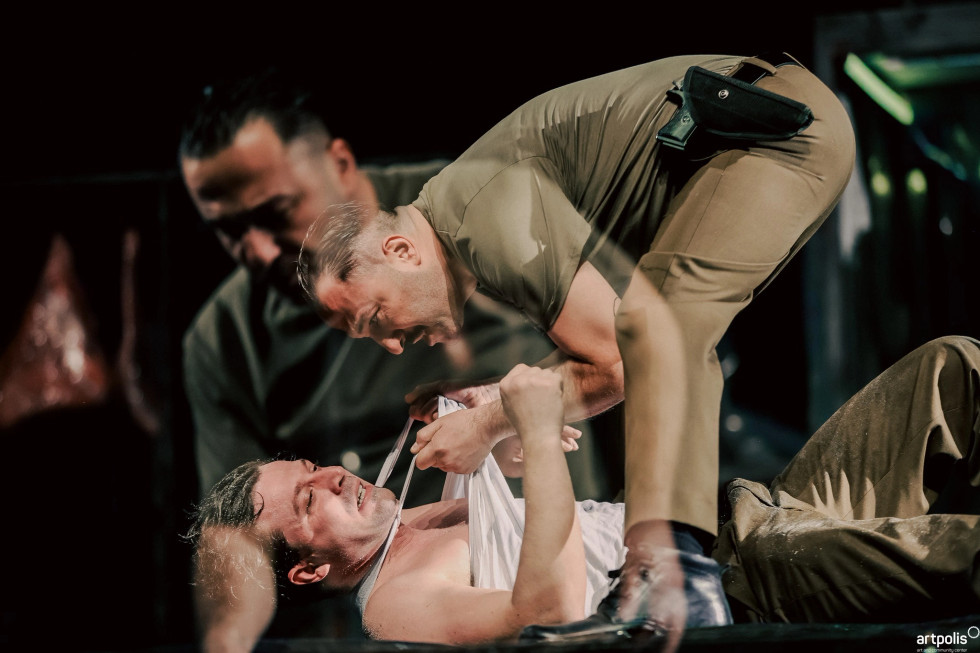

Por përballë kësaj qëndron një botë tjetër – ajo e kabaresë, e cila është më shumë se një lokal. Është një sistem. Një ritëm. Një mënyrë për të harruar. MC e përkufizon këtë filozofi me brutalitet kur këndon: “Parja botën rrotullon”. Dhe papritur, gjithçka bëhet mall – dashuria, trupi, ëndrra, shpresa. Shiten vajza ruse, japoneze, franceze, amerikane… dhe pastaj kosovare “të reja dhe të paprekura”.

“Njerëzit s’janë zhdukur vetëm nga plumbat. Janë zhdukur edhe nga pazaret. […] Me informata. Me shpresë të rreme. Dikush ka bërë tregti me fatin e të zhdukurve. Heshtje”. Këto fjalë të Sonit, të drejtuara ndaj Ernestit, janë akuzë e hapur. Ernesti (dhe MC) bëhen personifikimi i kapitalizmit primitiv të paqes – tregtarë të dhimbjes që blejnë dhe shesin heshtje, shpresë, kohë.

Në këtë botë, liria nuk është më një e dhënë. Ajo bëhet diçka që duhet negociuar çdo ditë. Kjo shfaqet qartë në përballjen mes Aidës dhe MC-së, kur ai i thotë me qetësi: “Këtu rehatinë e ke veç kur ta lejon dikush”.

Dhe më pas, si një ligj i heshtur i realitetit të ri: “Njeri? K’tu njeri bëhesh… veç kur t’lejojnë.”

Pikërisht këtu shfaqja ngre pikëpyetje: çfarë vlere ka liria nëse dinjiteti varet nga leja e dikujt tjetër? Dhe çfarë do të thotë të mbetesh njeri në një vend ku gjithçka mund të blihet?

Por “Kabare 1999” nuk është vetëm kaos. Brenda saj ka një dëshirë të fortë për të jetuar. Ajo shfaqet në mënyra të vogla, të papritura, ndonjëherë të brishta, por me humor e plot dashni. Në dashurinë e vonë mes Afërditës dhe Agimit, që duket pothuaj naive, por që është një akt i heshtur rezistence ndaj vetmisë. Në marrëdhënien e ndërlikuar të Dudijes me ushtarët e huaj, ku mbijetesa dhe mirënjohja përzihen në një zonë morale të paqartë. Në vetë Aidën, që vazhdon të shkruajë edhe kur e kupton se historia e saj nuk është më vetëm për të zhdukurin, por për ata që përfitojnë nga mungesa e tij. Këto nuk janë histori heroike. Janë përpjekje për të jetuar. Për të dashur. Për të mos u shuar.

Zymtësinë e përditshmërisë së pasluftës personazhet e ndrydhin dhe jetojnë mes dashnisë, seksit e qejfeve në Prishtinën që përqafon individualitetin e atyre që guxojnë, edhe pse të goditur ashpër nga lufta për mbijetesë (Foto: Rilind Beqa)

Jetë që nuk dorëzohet plotësisht

Për aktoren Semira Latifi, që e luan Aidën, formati i kabaresë ia ka lehtësuar procesin e krijimit të personazhit, teksa beson se shfaqja do të ketë jetëgjatësi.

“Mundem me thënë që kjo na ka ndihmuar shumë (formati kabare), na ka lehtësuar shumë për ta ndërtuar një personazh, e ka plotësuar personazhin shumë, si personazhin tim edhe të gjitha personazhet e tjera të cilat kanë skena së bashku, kanë storie së bashku. Është një formë e mirë e aktrimit ku secili aktor mundet me shfaqë talentin e vet në formën më të mirë të mundshme para publikut e që sonte ndodhi që publiku e priti tepër mirë, reagimet ishin tepër të mira edhe mendoj që është një projekt i cili ka me pas një jetë të gjatë edhe një publik shumë të fortë brenda vetes”, është shprehur ajo.

Kurse aktorja Aurita Agushi është shprehur se aventura e këtij produksioni veçse ka nisur.

“Jam e stërkënaqur (me reagimet e publikut) sepse aktori në skenë e ndjenë energjinë e publikut. Ia ndien edhe frymëmarrjen, ia ndien edhe energjinë. E di që aventura jonë veç sa ka nis edhe ka me qenë shumë e bukur me krejt ata bashkë që kanë me ardhë me pa këtë spektakël”, ka thënë Agushi, që luan në rolin e zonjës Afërdita.

Në fund, shfaqja nuk ofron një përgjigje. Ajo nuk e mbyll plagën. Nuk e shpëton askënd plotësisht. Por, ajo na lë me një ndjenjë të fortë: se jeta, edhe kur është e çrregullt, edhe kur është e ndotur, vazhdon të kërkojë lumturinë.

“Kabare 1999” na sjell Kosovën e pasluftës jo si heroizëm të ngrirë, por si jetë e gjallë, e çrregullt, por ende e padorëzuar plotësisht.

“Mirë se vini në kabare. Dhe mos harroni – drita fiket kur vendosim ne”.

Recent Comments